'Pandemic Seems Over, We are in For the Long Haul of Endemic'

What signifies the end of the COVID-19 pandemic? Virologists say the pandemic started in a staggered manner and will also end the same way resulting in a pan-endemic stage

More than two years have passed since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic. Since then, more than 493.6 crore people have been infected by the virus and more than 60.1 lakh people have died, according to data from Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.

Generally, while it takes years for a vaccine to be made and distributed, COVID-19 vaccines were developed, tested, and administered in only 11 months. Around 64.5% of the world's population has received at least one dose of the vaccine, data from Our World in Data show. In India, 84.4% or 79.28 crore adult eligible population had received both doses of COVID-19 vaccines by March 30, 2022, Union Health Minister Mansukh Mandaviya told the Rajya Sabha on April 5, 2022.

While many countries across the world faced more than three COVID waves, India was struck by three deadly waves which claimed more than 5.21 lakh lives in the last two years. While COVID-19 cases have spiked and fallen during each wave, India's cases plummeted to less than 1,000 new cases for the first time in two years on April 4, 2022. Does this mean that the COVID-19 pandemic is coming to an end?

Although there is no standard global definition for the end of a pandemic, health experts FactChecker spoke to stressed that the gradual burning out of pandemic will only happen as the transmission of the virus weakens. They highlighted how the global health crisis is not just a biological event but also a social, political and economic one – in which local governments are responsible to take the final call.

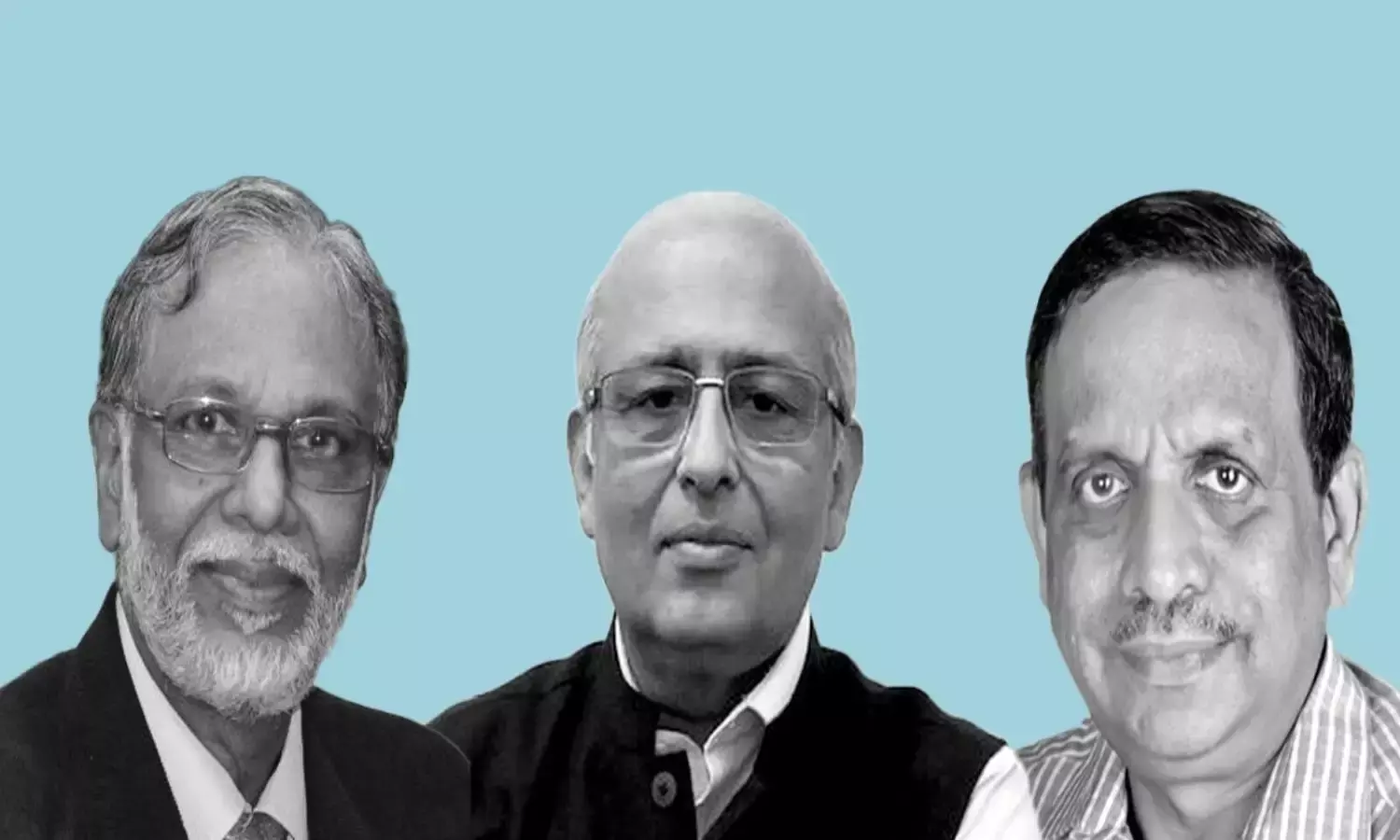

To understand what signifies the end of a pandemic, FactChecker spoke to Dr T Jacob John, virologist and professor emeritus at Christian Medical College, Vellore, Dr Shahid Jameel, virologist and director of the school of biosciences at Ashoka University, Haryana, and Professor T Sundararaman, former dean of the School of Health System Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences.

Edited excerpts:

Many countries, including the UK, lifted most COVID restrictions. Do such decisions signify the end of the pandemic and what parameters go into the decision making?

Dr T Jacob John: We are dealing with a directly person-to-person transmitted infectious disease. The effect of immunity among people could be seen, as the first wave settled without any vaccination at all. When the Delta variant began spreading, it was actually like a second pandemic: previous immunity against the first wave viruses (Wuhan-D614-G and Alpha) was ineffective and until Delta immunity modulated transmission efficiency, the wave rose and then fell to low and steady numbers for 25 weeks. The pandemic was technically over but Omicron came, which was like a third pandemic and the third wave went up and came down. By February 17, 2022, the Omicron wave gave way to the endemic. Globally, Omicron was the last wave. What do we expect? Immunity level in populations is the highest ever. We have vaccine-induced immunity also to top up infection-induced immunity. Now, no variant of the past can cause a wave of any magnitude. So, we believe the "pandemic" is over and we are in for the long haul of endemic COVID-19.

T Sundararaman: Pandemic ends when epidemic transmission of it ends. Which essentially is measured as R0 (R naught is the basic reproduction ratio which is an epidemiological metric used to measure the transmissibility of infectious agents). But it also means that it is declining and new hospital cases have become low and are declining for a period of time. However, there is no absolute criteria. So, it is also a judgement call. This could reverse if a new variant takes over.

Dr Shahid Jameel: Pandemics are not just biological, but also social, political and economic events, and therefore the end must also be as much of a social and political agreement as a biomedical one. At the global level, since WHO is the body tasked with declaring a pandemic, it is also the one to call it off. But several countries don't rely on just WHO guidance and have national and regional scientific advisory groups that rely on local surveillance and vaccination considerations. In England, considering the population 12 years and older, ~92% have received one dose, ~86% two doses and ~67% have received an additional booster dose. Researchers estimate that about 98% of the population has some immunity to prevent severe illness. Weighing against the economic effects, the government decided to lift all COVID restrictions.

How do global health agencies determine if we have reached the pandemic's end? For example, the Ebola outbreak was declared over by the WHO in 2020, but it flared up again. And then they re-declared it over in December 2021.

Dr John: Ebola transmission is not like SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Infection in social contacts is not 'inevitable' for Ebola but it was for SARS-CoV-2. That was why Ebola did not go round the world. Ebola returns again and again as zoonosis and then makes outbreaks. SARS-CoV-2 entered the human population just once and thereafter there was no second zoonotic episode. There could be a second zoonotic entry of an "animal recycled variant". Further zoonotic episodes are extremely unlikely. So, we are back to square one -- like the pre-pandemic period when we did not expect a pandemic but faced it when it came. We have vaccines in our armamentarium too.

T Sundararaman: Declaring an end to the pandemic is no guarantee against its flaring up again. If the virus hits a non-immune population group, or if an immune escape variant occurs, it will flare up. The declaration of a pandemic end will therefore be always tentative.

Dr Jameel: The WHO does this based on consultations with experts on its International Health Regulations Emergency Committee. This group advises the WHO Director-General on if and when to declare a pandemic's end. This is done taking data for infection and disease surveillance and vaccination into account as well as the nature of infectious pathogens and demographics. The decisions can only be as good as the available data.

What role does the immune system play in the gradual burning out of the pandemic?

T Sundararaman: If the number of people immune in the population is above the herd immunity threshold, which itself is related to the R0 factor, the pandemic burns out. But one could still have substantial sub-groups which are non-immune. The immunity could be through vaccination or through acquiring the infection or a combination of both. This immunity could decline over time or it could be lifelong.

Dr John: Scientists did not expect immunity to be ineffective to protect against re-infection, or to be vulnerable to waning in the short term. Yet, immunity caused the end of each wave: as I said before, immunity results in reduced transmission efficiency by the re-infected; its mass effect is that the epidemic abates and gives way to endemic virus survival among us.

Dr Jameel: As more and more people get infected and/or vaccinated, they become resistant to disease. They can sometimes get infected, but the amount of virus in the infected person is lower and thus not transmitted as well. This slowly leads to decline in transmission and burning out of the pandemic. But new viral variants that can escape immunity or are more infectious can overcome immunity a little better, causing spikes in infection rates.

Until now, only two diseases have been eradicated; smallpox and rinderpest virus, as per the WHO. What are the factors that lead to an elimination of a disease, as per history?

Dr John: Yes, only those two have been eradicated. One exclusively human and the other exclusively animal. Firstly, hosts should be one or very limited host species. Flu cannot be eradicated because birds, pigs, horses and humans are hosts. Factor 2: good vaccine(s) should be available that do two things — protect the vaccinated from diseases and affect the transmission efficiency. On this count, no COVID-19 vaccine seems to fit the bill. But there is more to the eradication story. Wild type 2 poliovirus was eradicated in 1999 but the vaccine WHO is using — Sabin type 2 — caused polio and even seeded outbreaks and for that reason type 2 polio has not been eradicated.

Dr Jameel: This disease' eradication was brought about by massive global vaccination drives, but also other containment and quarantine measures. Equally important is the fact that both of these viruses have no other animal hosts and can therefore not go to hide in another animal reservoir. Polio would be the next disease to be eradicated – again driven by vaccination against a virus that can only infect humans.

Since measures are being taken by every nation, even if the pandemic is curbed in one part of the world, it may continue in other places, like currently in China. What does this mean for the end of the pandemic?

T Sundararaman: That this pandemic's end is tentative – a combination of natural infection and vaccination and change in virulence should make it less of a public health threat. But for any respiratory virus with epidemic potential there is no guarantee of this.

Dr John: The pandemic started in different countries in a staggered manner and logically it would also end in a staggered manner. The COVID-19 will then be "pan-endemic" meaning endemic in all geographic regions/countries.

In the age of global air travel, climate change and ecological disturbances, people are constantly exposed to the threat of old and new diseases. History has shown us the great resilience of pathogens like how plague bacterium is still among us. Does COVID-19 hold similar chances?

Dr John: Plague bacilli survives among sylvatic rodents and very occasionally jumps to humans. We have them in Himalayan foothill forests, like in Himachal Pradesh. SARS-CoV-2 has never been seen in any other vertebrate hosts, even bats. So, its origin remains unsolved. But COVID-19 need not jump species again, it has become very much "domesticated" as our own human pathogen, now endemic. The threat of new, emerging infections, even pandemics, continues.

Dr Jameel: COVID will in all probability become endemic just like earlier coronaviruses that cause the common cold in humans. But all those factors – ease of travel, climate change and changing ecology – will continue to throw more novel infectious agents our way. The key would be to stop these in animal populations before they get to humans, and if they do, to have the right tools to contain them. Surveillance and a One Health approach would be key.

Going forward, how should we change our approach to the virus?

Dr Jameel: We must remain wary of newer variants, for which continued surveillance is necessary and continuous use of vaccines optimally. But the lessons from COVID should inform us to plan for the future. India is a good example of how prior vaccine manufacturing capacity helped us vaccinate a large fraction of the population. Improving health systems, local capacity and more investments into research and development are the way forward. India also needs a US CDC-like central command structure and empowered state health departments to manage disease outbreaks. The Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme and the National Centre for Disease Control need strengthening with highly trained professionals to be ready with surge capacity, which was missing during the second wave.